Travel Blogs

20 May, 2016 | Australia

It’s six weeks since I left Los Angeles, at 10:30pm Monday March 28, and landed in Sydney 15 hours later, at 6:30am Wednesday the 30th. It was Spring in California and Autumn in Sydney, but it felt pretty much the same, weather-wise.

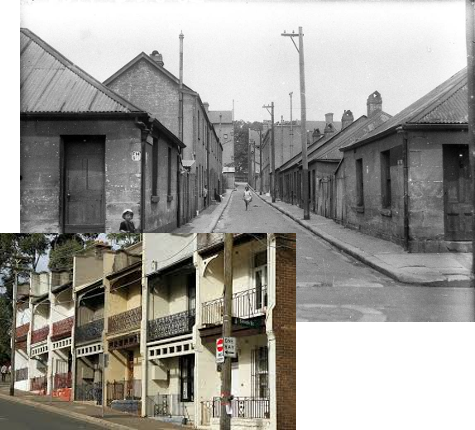

I went straight to my sister Jan's house, in Surry Hills. It used to be the slums, but, like in so many big cities, the inner suburbs of small cottages for the workers are now thoroughly gentrified.

Surry Hills in Sydney when it was slums in the 1930s, above; and some Victorian houses that now probably sell for two million-plus dollars.

I went to prison the next day, my annual visit to Long Bay with Anna Carmody, who goes in there every Tuesday and teaches several groups. I’m always glad to see my friends there.

|

With Anna during our lunch break in between classes at Long Bay, above.No one likes being in prison, I’m sure, but when I tell my Australian friends that the sentencing and the conditions in US prisons are so much worse, it’s not much of a consolation. According to a story in The Washington Post, July 7 last year, “A. . .reliable way to compare incarceration practices between countries is the prison population rate. . . . [T]he United States had the highest prison population rate in the world, at 716 per 100,000 people. |

“More than half the 222 countries and territories in the World Prison Population List, by the UK-based International Centre for Prison Studies, had rates below 150 per 100,000. . . . Australia has 130 per 100,000.” And it’s an established fact that the United States has 5% of the world population but 25% of the prison population. And, I remember reading, they have 50% of all lawyers on the planet! They’re in the right business, that’s for sure.

The next weekend, April 1–3, I went to a Sakya group in Milton, Manjushri Buddhist Centre, several hours south of Sydney on the coast. I stayed with Chiaki Ajioka, a new friend.

With Chiaki in the bush, in Milton, NSW.

Then back to Sydney to work with Yantra de Vilder, a composer, on our prayer project. Three years ago she was at a course in the Blue Mountains and after she heard me singing the prayers she said she “recognized a trained voice.” We started on this in August 2014 (see Postcard 44), and only now have we finished. Next step is the CD. As I mentioned earlier, we’ve taken typical Tibetan prayers and have recorded me singing multiple voices and multiple parts, not typical Tibetan at all. I want to call the CD “Devotion” and to offer it, at least in my mind, to Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

With Yantra, recording our prayers in her studio in Avoca Beach, north of Sydney.

Yantra told me that I have perfect pitch. I had no idea. What I do know is that I’m very attached to sound! At pujas, etc., where we’re supposed to feel devoted and be moved by the prayers, which are sung, of course, my attachment to my version of a nice sound is so strong that most of the time I’m miserable! The Tibetans don’t have notation, so everything is by word of mouth, so inevitably the tunes are mostly sung not in tune, or made up tunes, or are plain flat. I’m so intolerant! I go nuts.

My mother taught me to sing when I was a girl, as I mentioned in Postcard 21. My sisters would all go off to watch South Melbourne – the Swans – play Australian Rules football, but I couldn’t stand the shouting and yelling so I’d stay at home and study singing. I loved it. She sent me off to London when I was 23, but I decided I needed to stop wanting to achieve something and stopped studying. I was a disaster anyway. I didn’t study, actually, and made a total mess of an audition at a famous school in London; can’t remember the name now.

The week starting April 11 I spent in Melbourne, staying first at Julie’s in Carlton, as usual, and then at Mark and Jill’s place in South Caulfield, just down the road from 16th Street Studio, the acting school run by fellow student of Rinpoche’s, Kim Krejus. For the third year in a row I did an evening class for the students. I love actors! They totally want to understand the human mind, so they really enjoyed the Buddhist approach.

I wonder what kind of imprints they leave in their mind and therefore the karma they create and, therefore, what the results would be. Given that Buddha says that every millisecond of whatever goes on in our mind leaves seeds, and that these seeds will necessarily ripen in the future as our experiences, then it’s reasonable to think about this. There you are, with as much energy and authenticity as possible, replicating all kinds of people’s thoughts and behavior. That has to leave imprints in the mind. It seems to me, the key to whether or not acting the role of a harmful person leaves negative imprints in the mind depends upon the motivation impelling the actor’s acting. Otherwise what?

With, from left, sisters Polly, Marie, Julie and Judy at Shakahari Restaurant in Carlton, at the earlier version of which on Lygon Street, in March 1976, I saw the poster advertising the retreat with Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche that turned out to be my first Buddhist teachings.

This is the key point to understand: the main cause of whatever karma we create, and therefore the result that ensues, is the motivation, not the action itself.

This is why Lama Zopa Rinpoche never stops advising us to insert a bodhichitta motivation into everything we do. It sounds so abstract to us: what do you mean, “do everything with bodhichitta?” It’s clear I haven’t got it, we think, so I can do something with it?

But when we understand the mechanics of karma – it’s a natural law, remember – then it makes sense.

Everything we do is driven by the intention to do it – this is the fundamental meaning of the word “karma” or “action”: mental action is the first step: “I will.” But what we don’t notice is the motivation, the reason, that impels the intention. Being in samsara, being an ordinary person, the usual motivation is attachment. It’s so ingrained, so instinctive, that of course we don’t notice it! It’s natural. That’s why most actions we do – eating, sleeping, going to the toilet, walking, talking, going here, doing that – whatever! – are causes for samsara. This is the logic of Buddha’s analysis of the mind and how we create our own suffering and happiness.

And it’s because of this that consciously inserting a bodhichitta motivation into the action before doing it – something as simple as, “I am eating this food so that I can be healthy so I can benefit others” – literally changes the character of the action and thus the result. When we understand this, we will want to insert that motivation into everything we do! The logical result of this, simply because we’re creatures of habit, is that it’ll become our habit; it becomes the cause for actually accomplishing bodhichitta eventually.

-----

During that week I also spent some time in Wonthaggi, in Gippsland, east of Melbourne, with some kids at some special school. They were great. We had good conversations about the mind. They go there for education but also they hang out, use the computers, eat a meal. It’s a friendly environment, which many of them totally lack of home.

I heard about a school in some poor part of Melbourne that had disastrous results for their students, plenty of truancy, etc. The principal struggled and succeeded to get funding to open the school really early and provide breakfast for the kids, as well as nice environment, a place they’d like to spend time. Result, obviously, was lots of enthusiastic students and better results. It’s a no-brainer.

In the same week I also visited a Sakya center in Warragul. And the Sunday after 16th Street was at Shirani’s yoga centre near Woolamai, southeast of Melbourne. And then two hours north to Atisha Centre for the next week, for the annual retreat we do together.

With Tom, who organized the visit, and some of the kids at the Bass Coast Adult Learning Centre in Wonthaggi, east of Melbourne. Above left, we’re getting the thumbs and, above right, the finger! Below, in Warrugal with the Sakyas.

|

|

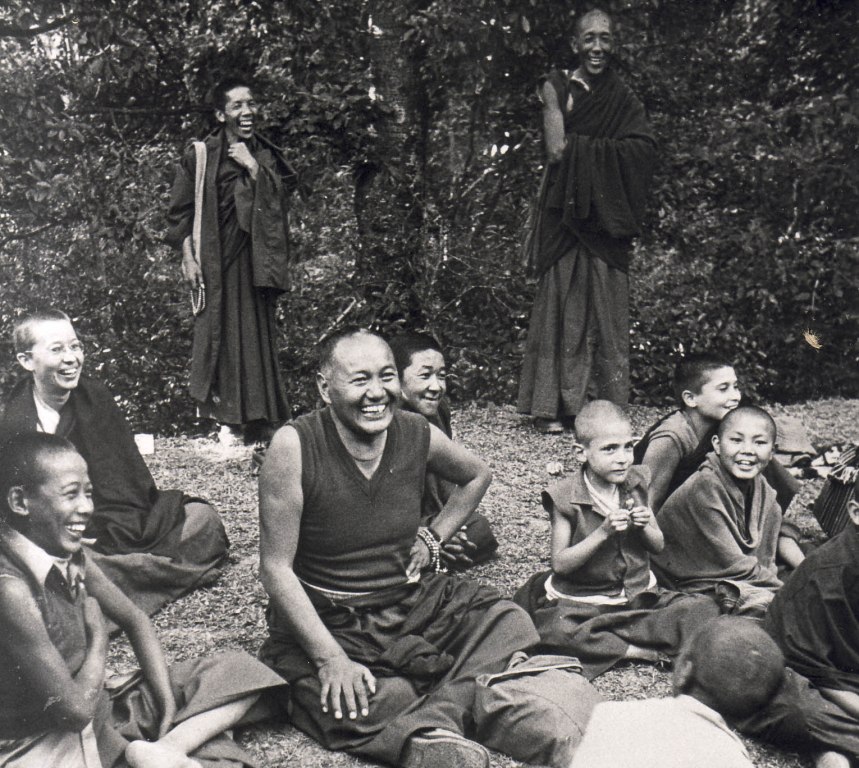

Lama Zopa Rinpoche with the young Ling Rinpoche, left, and the Junior Tutor Trijang Rinpoche, left, and Senior Tutor Ling Rinpoche.

From May 2 for three weeks I was in Queensland. It’s meant to be autumn in Australia, but everywhere it’s so warm, especially in tropical Queensland, which is Australia’s Florida.

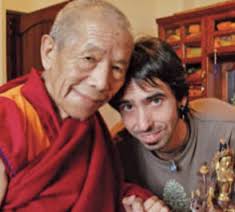

The reincarnation of the Senior Tutor of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Ling Rinpoche, gave a teaching the first weekend: I was so glad to be there. He’s one of a whole group of young lamas, the reincarnations of our lamas’ lamas whom we had the incredible good fortune to meet in the 1970s and 80s.

Lama Yeshe made sure we made connections with these holy beings, in particular at the amazing months-long event in India and Nepal that Lama called the Enlightened Experience Celebration, or as we’d often refer it, the Dharma Celebration. The first was in 1982. Many of us spent the entire six months at it, steeping ourselves in extraordinary teachings from these holy beings, including Ling Rinpoche.

Lama Zopa Rinpoche mentions him in his book about death and that he spent 13 days in meditation after passing away.

The young Ling Rinpoche mentioned at the beginning of his teachings on Lama Tsong Khapa’s Three Principal Aspects of the Path that the old Ling Rinpoche had a close connection with Lama Zopa Rinpoche, and that as a young boy Lama Zopa would visit Ling Rinpoche in Darjeeling and play games with him. We were speculating later whether the young Ling Rinpoche remembered this from his past life or was informed in this life!

Our group at Chenrezig Institute. Lama Zopa Rinoche has declared that he wants the center to make a new Thousand-Armed Chenrezig statue to replace the above one.

|

After Ling Rinpoche’s weekend we had a week’s retreat; followed by another week in Brisbane with Miffi and Eddie at Langri Tangpa Centre, my old mates. Miffi and Eddie waving me off to the airport in the early morning. |

Good news came from Lama Zopa Rinpoche on May 18: His Holiness the Dalai Lama has recognized the reincarnation of Lama Lhundrup, Kopan Monastery’s beloved abbot. He’d been at Kopan since 1972. The story goes that Lama Lhundrup was studying with all the other Sera Je Monastery monks in south India when he received a letter from his guru, Lama Yeshe, who had recently started Kopan Monastery outside Boudhanath near Kathmandu, asking him to come and help. Sera Je’s abbot said he could go, but “come back quickly.” Well, he never came back.

Rinpoche said that Lama Lhundrup was “the heart disciple of Lama Yeshe, who is kinder than all the three time Buddhas, including Buddha Vajradhara. Lama Lhundrup was invited by Lama Yeshe to look after Kopan Monastery and was the principal teacher of the monks

|

|

and nuns, giving advice and looking after the Dharma discipline. Then after Lama Yeshe showed the aspect of passing away, Lama Lhundrup looked after the finances and with all his heart and life he looked after Kopan Monastery. It was from Kopan Monastery that FPMT started. Lama Lhundrup also dedicated and put effort into developing Lama Tsongkhapa’s teachings in Kopan and in all of Nepal.

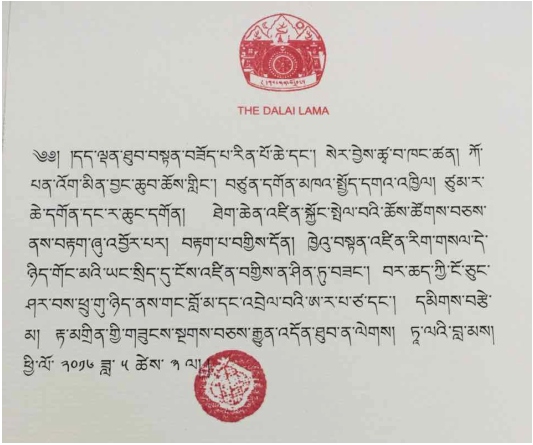

“Now Lama Lhundrup has been recognized by Buddha Chenrezig His Holiness the Dalai Lama, who said 'Tenzin Rigsel to be recognized as a reincarnation of the late (Lhundrup Rigsel) comes out extremely positive.'

“What made Lama Lhundrup to have this special reincarnation was his pure morality, compassion to sentient beings and wish to liberate all sentient beings by spreading the teachings of Lama Tsongkhapa. I think this incarnation will be continually more and more beneficial as his life goes on and also as his lives go on.”

Lama Lhundrup, standing on the left, and Lama Pasang on the right, with Lama Yeshe and some of the first Kopan monks, and Ani Karin, in the mid-1970s.

|

Lama Lhundrup with Lama Osel, Lama Yeshe’s reincarnation; a painting of the old gompa at Kopan by one of the monks in the early 1980s. |