Travel Blogs

25 January, 2016 | Colombia

A pre-dawn drive with Violette and Francois from Marzens to Toulouse airport got me to my plane for London. I had a six-hour wait, which is not unusual. Because I have so many miles in my Qantas plan, I get to stay in the first class lounges at the airports, some of which are like 5-star hotels, believe me! (I talked about these in postcards 29 and 49.) If I need a sleep, so many airports these days have hotels onsite.

Then on to Boston in the afternoon on British Airways, arriving in the evening, an eight-plus hour flight. I arrived in time for Lama Chopa: I was happy about that. Damchoe leads it. He’s an ex-Kopan monk and the translator here for the past twenty years.

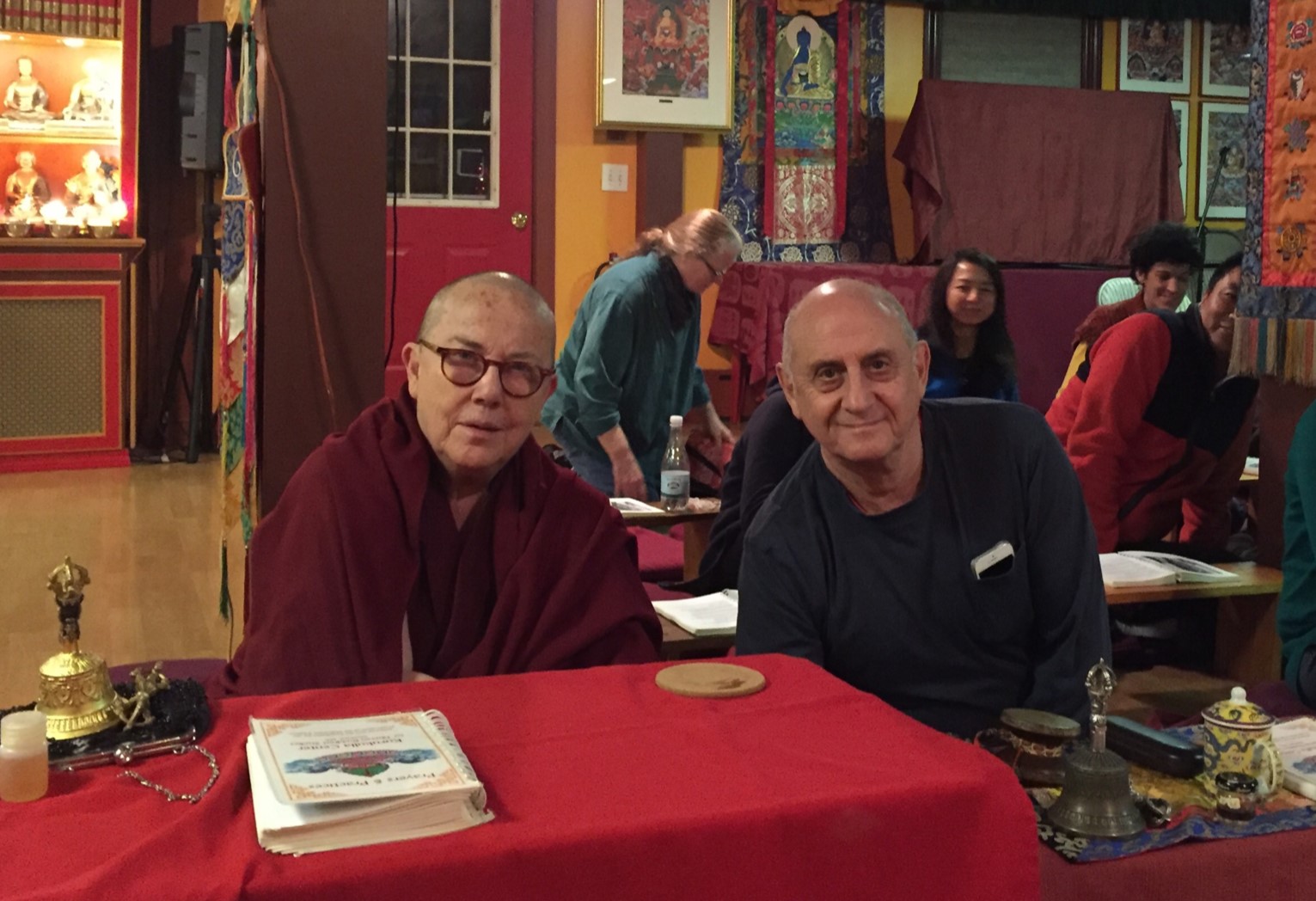

Damchoe with Ven. Roger during the most recent visit to Kurukulla Center in Boston of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, 2014.

Kurukulla Center has had two visits from His Holiness the Dalai Lama. That’s unusual for sure. For the last visit, a couple of years ago, Sean the director got several neighbors to open up their back yards to make one continuous area, under canvas and full of chairs, for the hundreds of visitors.

The mayor of Medford, greeting His Holiness at Kurukulla in 2014. It seems that Kurukulla’s geshe is holding a key, which I assume is the key to Medford. Lucky Medford!

I was in Boston for two weeks. On one of my days off I visited Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive, in the suburbs, and had lunch with Nick Ribush and Wendy Cook. Nick was my first boss in the FPMT. I’d met him soon after my second course with the lamas, in 1977. He was sent to Australia from Kopan by Lama Yeshe to lead some courses called Kick the Habit – a great title, actually; I wonder why people don’t use it more often at the centers?

I figure that Lama felt that Nick’s training as a medical doctor gave a course entitled that more credibility. I remember I helped him out at the course in Melbourne. I also remember that it was then the penny dropped for me that I should go to Kopan Monastery and become a nun. I went to the 1977 November course. As I discussed in various postcards (1, 7, and 44), I started working for Nick there, basically carrying on the job I had done all my life: editing, printing, publishing, etc.

I’d been working with words since I was young. My father, a journalist, started a printing company that eventually employed the entire family, my mother and us seven kids. It was my apprenticeship. We learned everything: design and graphics, plate-making, typesetting, and writing.

With Nick Ribush at Tara Puja at Kurukulla Center in Boston. He was my first boss in the FPMT, working for Wisdom at Kopan Monastery in 1977; and then again from 1983, in London.

Later, as a political activist I was always involved on the propaganda side of things: the posters, the newsletters, the books. As soon as I met Lama Yeshe and Rinpoche, at Chenrezig Institute in 1976, and I heard we needed to do karma yoga, I naturally gravitated towards transcribing the teachings. Nothing had changed: still the propaganda side of things!

As soon as I got to Kopan to become a nun I made a beeline for the publications office. I was in heaven. When Nick eventually asked me if I’d like to work for Publications for Wisdom Culture (Lama Yeshe’s name for what later got called Wisdom Publications), I thought to myself, “Why is he asking? It’s my job!”

I remember one of the first jobs I did for Nick was in New Delhi – Lama had sent him there to run Tushita Meditation Centre and me to work with him on publishing. It was a fundraising booklet about Sera Je Monastery. I was brand new, of course, but I was quite confident I could do a good job. Well, he rewrote it all! In the end I designed the thing and organized the printing of it. I was proud of my efforts, and even moreso when Rinpoche praised the shape of it: it was horizontal, like a pecha, not vertical like normal Western books.

Then Lama moved Wisdom to the north of England. My main job was taking care of design and production but somehow it gradually included editorial. And by the time we moved to London and Nick had come from India to run things again, in 1983, my job included both aspects. For me, now, I can’t separate them: when I look at a book or magazine or newspaper, simultaneously I’m taking in the look and the feel of it, the paper, the binding, the typesetting, the design, the editorial structure – the architecture of the content – and finally the writing.

The point of all of it, of course, is to make the reader happy. First, that book on the shelf among the hundreds of others needs to grab their eye. Then the title: it needs to accurately inform but also energize. The feel of it must be pleasing. The paper should be nice to touch, the pages easy to turn.

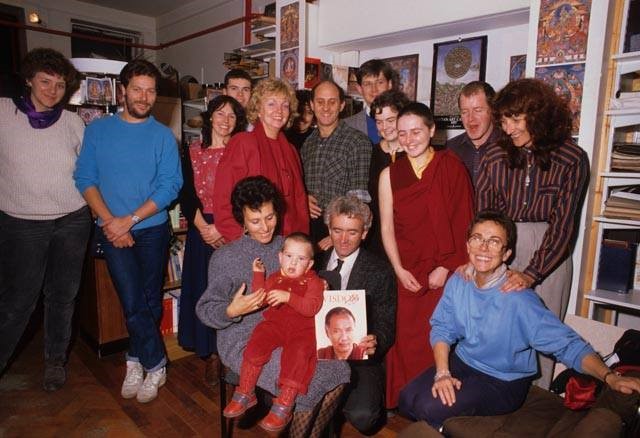

At Wisdom in London in the mid-eighties (I wore lay clothes in those days) with Nick, in the plaid shirt, and the staff, and Lama Osel and his parents.

All of this, of course, leads to the words themselves. It’s the editor’s job to make the words coherent and easy to digest, and then the designer’s job to make what’s on the pages clear and elegant and pleasing, to help the reader internalize and remember the instructions.

Of course, if the book is a novel, if the words describing the people, the story, are compelling enough to grab the reader, then design doesn’t matter. But for Dharma books, for example, that are hard to digest, that don’t grab the reader’s fantasties like novels do, the way things are presented is crucial.

It’s these two processes in particular – editing and design – that over the years of working with books I’ve found impossible to separate. The designer can only work with what the writer gives them. So if there are pages and pages of long paragraphs, no headings, no structure, the designer’s hands are tied. The words are indigestible.

So the writer/editor must anticipate the needs of the reader, how to help them easily take in what’s being said by imagining the look of the pages, including headings, for example, that function as reminders, as signposts of where the reader is in the process, and as a summary of the advice.

I remember working on the editing of Pabongka Rinpoche’s Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand when I worked for Wisdom back in the 1980s. A huge book, masses of information – masses of instructions, things to think and do. Keeping in mind what Lama Tsongkhapa says in his Hymns of Experience, that “all the scriptural texts are to be taken as sound advice,” it seemed to me that sometimes it’s very hard to extract the advice, to hear it clearly, when there are pages and pages of densely packed and often difficult-to-grasp concepts.

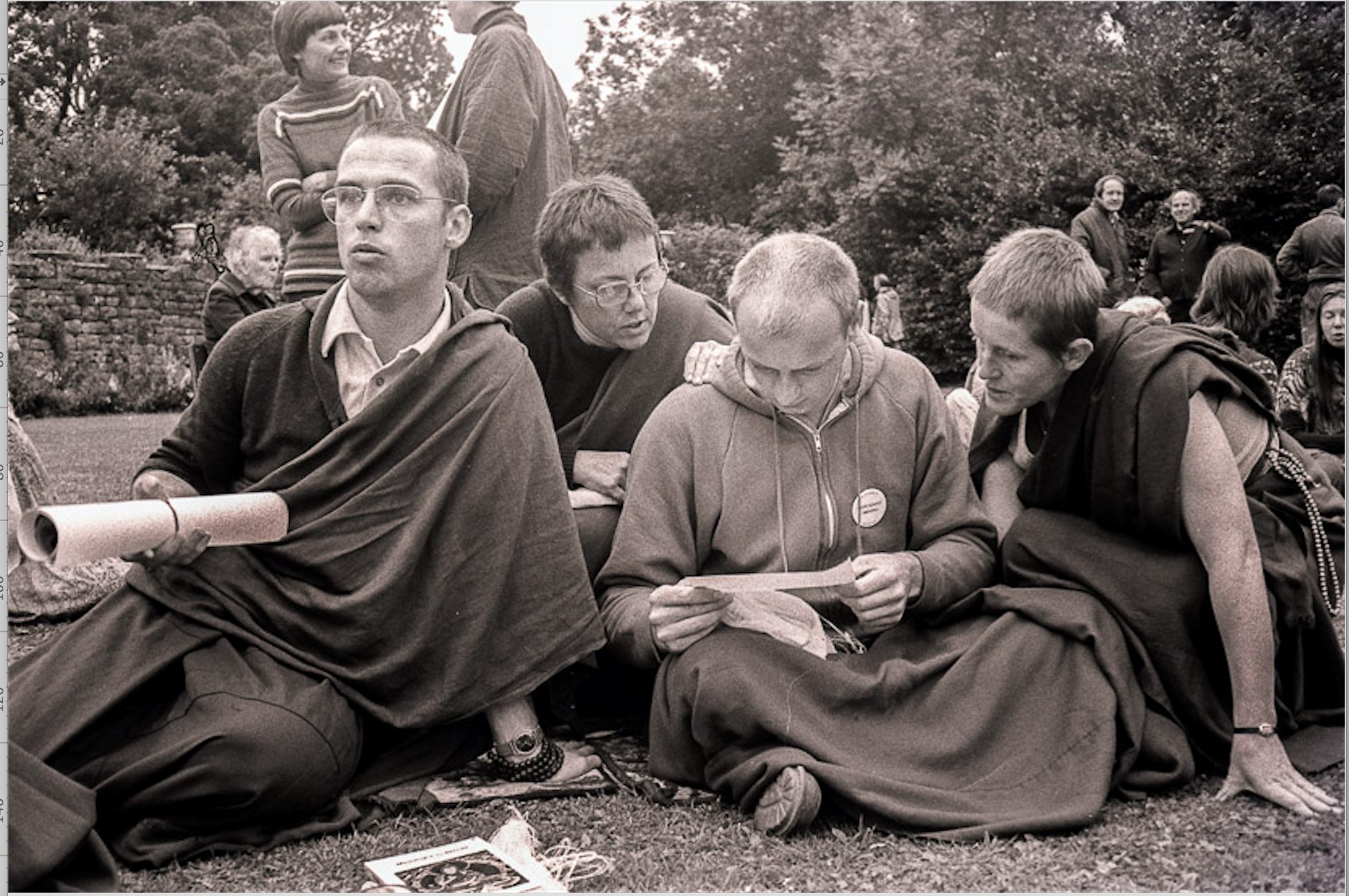

Pende, Neil, Olga and me after graduating from our Geshe Program year, 1982, I think, while I was working full time for Wisdom.

The outline is there, so helpful: the Tibetans are great at that! But sometimes there are twenty pages between headings and as you’re ploughing through you have no sense of where you are in the outline. You can’t take in the advice; there is so much.

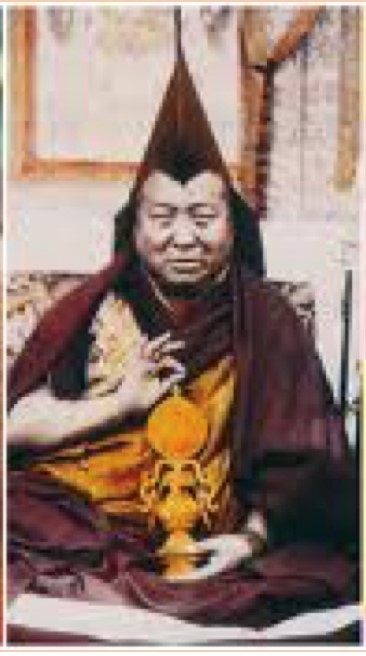

Pabongka Rinpoche, the author of Liberation, which I worked on in the 1980s.

It’s like a map: you need to see all the signposts as you go along: you’ve come this far, you’re here now, and you have this far to go.

So to help the reader know exactly where they are on that map, one of the devices we used was to show in the right-hand running heads the main topic that is on that particular page. In traditional publishing the right-hand running head is the name of the chapter, and that at least gives you an idea of where you are. But as we know, the editor of Liberation, the author’s main disciple, Trijang Rinpoche, chose to name the chapters according to the day – Day One, Day Two, etc. – not according to the topic. And that tells you nothing. So, being able to see “Day One: Karma,” for example, helps the reader know where they are on the map. (As I read everything on my iPad these days and haven’t seen a printed copy of the book for years, I don’t know if this still applies.)

If all the teachings are to be taken as sound advice, then Dharma books are actually manuals, handbooks: what to do when. That means they should be edited to read like a handbook and designed to look like one. Lots of parts, short tasty chapters, clearly delineated sections, plenty of experiential headings, bullet-point lists if necessary. Can you imagine a cookbook written in narrative form, long chapters with many different recipes in page after page of well-written sentences, but with few headings, no lists, no “Now do this” and “Now do that.” You’d never get a cake made!

In the Buddhist publishing world there seems be a tension between the idea of a practice book and a scholarly one, and the above approach, which I’ve come to think of as so crucial over the years, does not appeal to the scholars; it seems to insult the intelligence of the reader. But scholars are practitioners too.

Actually, several years before we published Liberation, we’d put out Jeffrey Hopkins’s Meditation on Emptiness, which employed the usual running heads. Later, after he’d seen Liberation, he expressed the wish that when his book was reprinted we’d use that style. And I notice now that he, a scholar among scholars, makes the books he edits experiential. Throughout His Holiness’s Mind of Clear Light: Advice on Living Well and Dying Consciously, a commentary on a poem by the First Panchen Lama, Hopkins adds pieces of “Summary Advice” every few pages, lists of numbered points of the previous material, to help the reader/practitioner remember and internalize the instructions. So, so helpful.

Anyway, this approach of course informed my work on Rinpoche’s amazing book about how to help at the time of death, which is now available from Wisdom (but structured differently; the original is available as a pdf from fpmt.org/death).

As I mentioned in the last postcard I’m now back working on Lama Yeshe’s beautiful teachings on Mahamudra, based on a short delicious text by Losang Chokyi Gyaltsen, an earlier Panchen Lama. I’ve promised Nick and Wisdom, who will publish the book, by the end of this year.

Lama offering food to beggars in Bodhgaya during the First Enlightened Experience, 1982.

In 1982, during Lama’s Enlightened Experience Celebration – a six-month Dharma feast of retreats and teachings with His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Ling Rinpoche, Song Rinpoche and others, for 700 Western students – Lama had requested His Holiness to teach on this text. It was extraordinary: in-depth and clear. Alex Berzin translated and edited it and it’s published now by Snow Lion.

------

Two weeks in Boston, then to Bogotá in Colombia on Monday January 18, via an overnight stay in Miami.

I’ve been coming here to Rinpoche’s Centro Yamantaka for twenty years. A nice group of people. Amparo took over from Olga soon after I left eighteen months ago. The first director was Mauricio, who now lives out of Bogotá with Fabio.

With Mauricio and Fabio in Bogotá.

On Wednesday I got an email from a guy called Manuel, who lived in Medellin, he said. He told me that he’d lived in Australia for a while – he studied tabla with a teacher in Melbourne – and had heard a bit of Dharma. He wondered if I could come to Medellin. I told him that it had to be either the following Saturday night – or 2018. Saturday night it was! He said he would invite a few friends to an old farmhouse near the airport and we could have a meal and a talk. Amparo came with me but our plane was cancelled and we eventually got there by 9:30. We had a very nice chat, 20 of us, and stayed the night. Very dear people!

At Medellin airport, with Amparo, director of Centra Yamantaka, Manuel, who invited us, and his friends Boris and Jenny.

Back in Bogotá Amparo took me to a dentist, Jesus, a student of Rinpoche’s. He did three fillings, and then announced at the end that I needed eight more and that he would do them when I came back. I hope my teeth last till 2018! Unlike in Australia, the US, etc., he didn’t have a nurse and he didn’t use anesthetic. Initially I was nervous, but there was no pain. Nevertheless, it’s a bit nerve-wracking experiencing that intense activity in your mouth!

On Monday January 25 I flew to Miami and then to Albuquerque in NM via Dallas Fort Worth to spend a week at Thubten Norbu Ling in Santa Fe.